On July 1, 2021, the world of college athletics changed forever.

For the first time, all National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) athletes in the United States are able to profit from their own so-called name, image, and likeness (NIL). While the winds to end amateurism have been blowing for a long time, the NCAA’s decision to alter the NIL bylaws came quickly.

One week, athletes couldn’t make money. The next, they could.

“This is an important day for college athletes since they all are now able to take advantage of name, image, and likeness opportunities,” NCAA president Mark Emmert said in the release. “With the variety of state laws adopted across the country, we will continue to work with Congress to develop a solution that will provide clarity on a national level. The current environment—both legal and legislative—prevents us from providing a more permanent solution and the level of detail student-athletes deserve.”

And they are racing to monetize this opportunity through a variety of methods: being sponsored by local companies, partnering with national brands, giving fans inside access, and selling merchandise.

Shopify for athletes

Jordan Bohannon is one example of a student-athlete making moves in this space. The 6’1”, 175-pound University of Iowa squad point guard is one of those classic NCAA characters, a guy loved by his teammates and fans and detested by the opposition.

On the evening of December 12, 2019, Bohannon walked off the floor of the Hilton Coliseum in just his socks. After scoring 12 points and helping his Buckeyes defeat their Iowa State Cyclone rivals, he took off his shoes, signed them “To ISU: Thanks for Memz.”, and left them on the three-point line. “I’m always about trolling,” he said after the game. “I’m always about getting stuff stirred up.”

Bohannon is a straight SAVAGE pic.twitter.com/tjTM12U2uq

— Lucy Rohden (@lucy_rohden) December 13, 2019

In past years, that would have been that: a short burst of media fame, a few laughs on social media, a college athlete being a college athlete, tapping into a competitive rivalry between schools. And, for a little over a year and a half, it was.

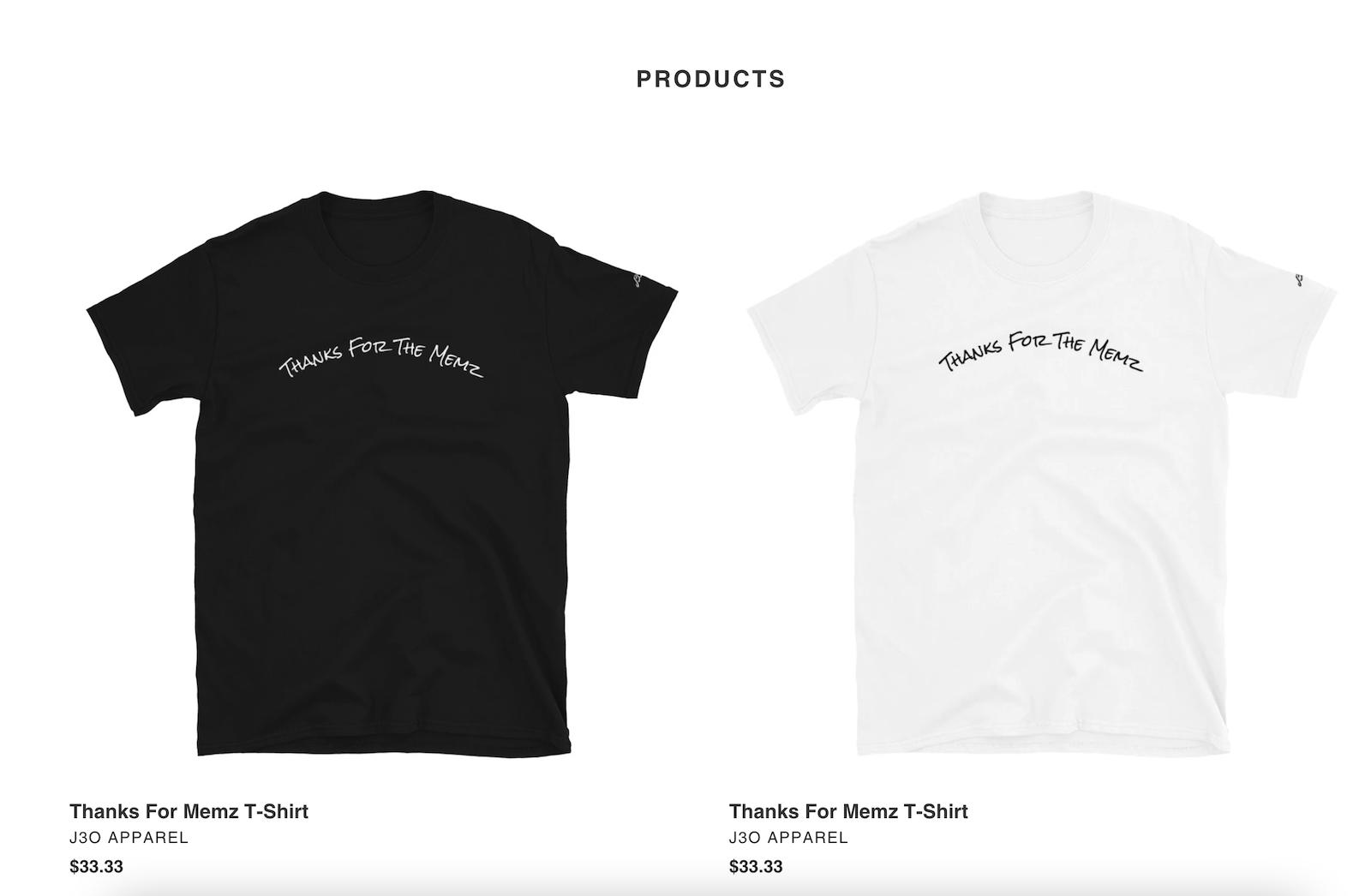

But Bohannon, an interdepartmental studies major with entrepreneurial aspirations, took advantage of the NCAA NIL rule change by launching a Shopify store called J30 Apparel. His first product? A simple white or black t-shirt with the words “Thanks for the memz” written on it, priced at $33.33 for the no. 3 he wears on the court.

“I figured that would be a great way to start [my apparel company], to show people I want to do something that holds meaning and is not just a random idea,” Bohannon said over the phone a few weeks after his drop debuted in July.

He sold more than 100 shirts in the first 24 hours, more than half of the 200 he made available. By the time we spoke, only a few remained. (In addition to t-shirts, he also hosts a podcast and offers services like a 10-minute shooting lesson for $110.)

NCAA’s NIL rule changes on July 1, 2021 represent a sea change, and there’s a potential financial windfall for those who understand the terrain and are inspired to take advantage. Bohannon is one of hundreds or perhaps thousands of college athletes making money because of this shift.

Athletes making NIL moves

There’s money to be made, especially for athletes with large audiences, either due to their position, the popularity of the team they play for, or the social media followers they have. University of Alabama quarterback Bryce Young is approaching $1 million in endorsement revenue and signed a deal to be represented by Creative Artists Agency.

Haley and Hanna Cavinder, better known as the Cavinder Twins, signed deals with Boost Mobile and Six Star Pro Nutrition, brands that were attracted to their status as star Fresno State hoopers, and also to their more than three million TikTok followers.

@cavindertwins wait for the surprise ##foryoupage ##bball

♬ The Chicken Wing Beat – Ricky Desktop

They even earned their own billboard in Times Square.

ON A BILLBOARD IN TIME SQUARE 😭 WHAT IS LIFE… blessed❤️ pic.twitter.com/ZyA4Uim5zB

— Hanna Cavinder (@CavinderHanna) July 1, 2021

Lesser-known athletes are also landing plenty of deals. Five Jackson State football players signed with 3 Kings Grooming products, and Degree plans to dish out $5 million in partnerships over the next five years. Arkansas wide receiver Trey Knox and his pet husky are sponsored by PetSmart.

Some teams are helping their players gain a foothold. The University of Southern California (USC)’s men’s basketball team designed logos for its players. Logos can lead to brands, which can lead to other monetizable items like merch.

Ahead of college athletes being able to cash in, some college athletic departments are helping design logos for their athletes. Here’s @USC_Hoops pic.twitter.com/1hQFXmA52H

— Darren Rovell (@darrenrovell) June 29, 2021

Shopify + athletes = ❤️

And now, a word from Johnny Manziel, the former Texas A&M University quarterback, bad boy, and all-around media superstar who would have made millions if the NIL rule was in place when he was in college:

Set up a business. Create Shopify account. Design merch w/ fulfillment to ship and handle customer service. Tweet/IG directly to your fan base. Make bank bros

— Johnny Manziel (@JManziel2) July 1, 2021

Bohannon, the Iowa point guard, set up a Shopify site to launch his t-shirt line. He used a third-party service to fulfill orders on-demand because it was easier and “college athletes don’t have a ton of time on their hands,” he said. There are many other athletes who are also getting into the merch game.

Ready to create your business? Start your free 14-day trial of Shopify—no credit card required.

Don’t forget the rules

The rapid rule change has led to a confusing variety of rules and regulations. Not every state has NIL laws in place, and while compliance departments at many universities can help, student-athletes are more or less on their own to navigate the space.

The newness of the NIL world can also create an opportunity for bad actors to take advantage of student-athletes. It’s better to pick and choose fair deals, but that can be difficult to do given the potential to make some quick and easy money.

There are over 380,000 student-athletes, and most of us go pro in something other than sports.

When it comes to merch, athletes do need to be aware of copyright and legal issues. Take the story of Florida Gator wide receiver Jacob Copeland. He designed a t-shirt that features the Gators orange and blue color scheme, but he cannot use the school’s logo unless he gets permission from Learfield IMG which owns the rights.

“Every athlete, just like any individual who conducts commerce, must be cognizant of the rights that must be cleared in order to sell anything,” said Darren Heitner, a lawyer who has worked on multiple NIL deals. “With regard to athletes specifically, they need to ensure that if they are going to use their school’s marks—the names, the logos of the universities, perhaps even the school colors—on the products that they are selling, they must receive the expressed written consent of the universities before doing so. Additionally, if they are going to include any photography or imagery that may have been created by some third party, they want to do what’s necessary to receive a license or other type of consent to use that, particularly in a commercial sense.”

We’re going to see quite a mix of opportunity and certainly more and more athletes who decide to be entrepreneurial and start their own business.

While these legal issues will not go away, it will become easier and easier for athletes to find information about how to avoid potential pitfalls. First-movers like Iowa’s Bohannon are educating themselves on the process and passing on their knowledge. Recently, he has been tutoring Michigan star Adrien Nunez, who has 140,000 followers on Instagram and almost two million on TikTok. Compliance officers at universities can help as well. Knowledge trickles down, the next generation of potential stars more aware of the ins and outs than the previous one.

It’s a new world, and the land grab is now.

The rise of the athlete entrepreneur

Here’s the truth: For the majority of college athletes, the change in NIL laws will not alter their lives that much. Playing a sport at such a high level is a time-consuming, exhausting endeavor, and building a business or pursuing sponsorships on top of sport is not for everyone. But they may benefit financially just by showing up—the University of North Carolina launched a group licensing program, for example—and athletes at big programs in large universities getting something just by showing up could become table stakes.

The bigger change is coming for the percentage of college athletes who want to parlay the huge platform they have into something larger.

“A lot of athletes are looking big picture, seeing immense opportunities, and doing more than just these one-offs in exchange for a set form of compensation,” Heitner said. “Certainly, those types of deals will always be a part of this ecosystem because they make sense, but I think we’re going to see quite a mix of opportunity and certainly more and more athletes who decide to be entrepreneurial and start their own business.”

Like the NCAA organization says, “There are over 380,000 student-athletes, and most of us go pro in something other than sports.”